What is the Linux File System?

Linux file system is generally a built-in layer of a Linux operating system used to handle the data management of the storage. It helps to arrange the file on the disk storage. It manages the file name, file size, creation date, and much more information about a file.

If we have an unsupported file format in our file system, we can download software to deal with it.

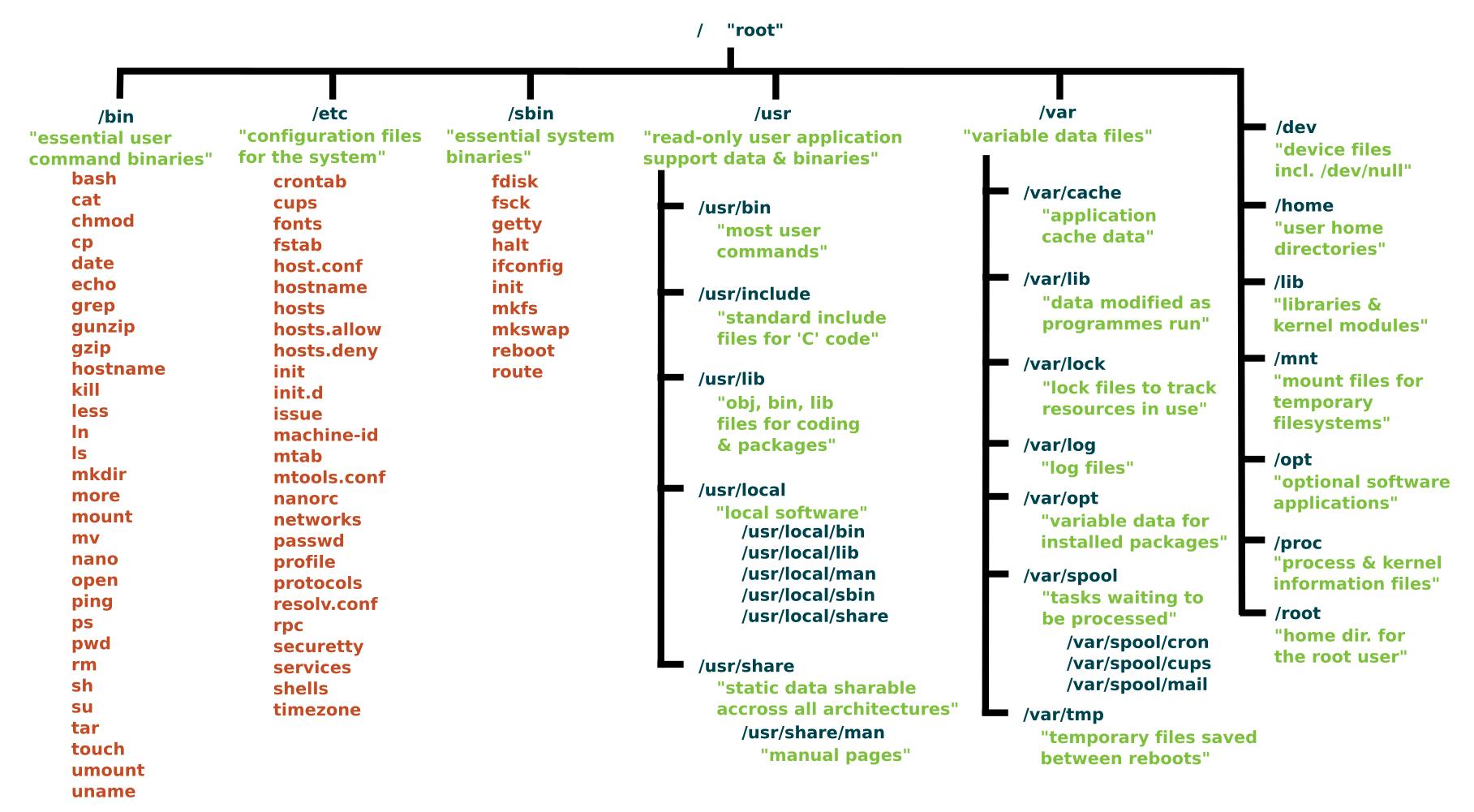

The Linux file system contains the following sections:

- The root directory (/)

- A specific data storage format (EXT3, EXT4, BTRFS, XFS and so on)

- A partition or logical volume having a particular file system.

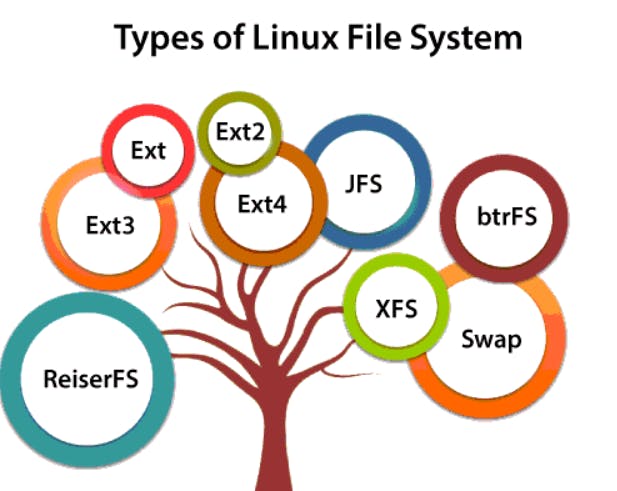

Types of Linux File System

When we install the Linux operating system, Linux offers many file systems such as Ext, Ext2, Ext3, Ext4, JFS, ReiserFS, XFS, btrfs, and swap.

When we install the Linux operating system, Linux offers many file systems such as Ext, Ext2, Ext3, Ext4, JFS, ReiserFS, XFS, btrfs, and swap.

Let's understand each of these file systems in detail:

1. Ext, Ext2, Ext3 and Ext4 file system

The file system Ext stands for Extended File System. It was primarily developed for MINIX OS. The Ext file system is an older version, and is no longer used due to some limitations.

Ext2 is the first Linux file system that allows managing two terabytes of data. Ext3 is developed through Ext2; it is an upgraded version of Ext2 and contains backward compatibility. The major drawback of Ext3 is that it does not support servers because this file system does not support file recovery and disk snapshot.

Ext4 file system is the faster file system among all the Ext file systems. It is a very compatible option for the SSD (solid-state drive) disks, and it is the default file system in Linux distribution.

2. JFS File System

JFS stands for Journaled File System, and it is developed by IBM for AIX Unix. It is an alternative to the Ext file system. It can also be used in place of Ext4, where stability is needed with few resources. It is a handy file system when CPU power is limited.

3. ReiserFS File System

ReiserFS is an alternative to the Ext3 file system. It has improved performance and advanced features. In the earlier time, the ReiserFS was used as the default file system in SUSE Linux, but later it has changed some policies, so SUSE returned to Ext3. This file system dynamically supports the file extension, but it has some drawbacks in performance.

4. XFS File System

XFS file system was considered as high-speed JFS, which is developed for parallel I/O processing. NASA still using this file system with its high storage server (300+ Terabyte server).

5. Btrfs File System

Btrfs stands for the B tree file system. It is used for fault tolerance, repair system, fun administration, extensive storage configuration, and more. It is not a good suit for the production system.

6. Swap File System

The swap file system is used for memory paging in Linux operating system during the system hibernation. A system that never goes in hibernate state is required to have swap space equal to its RAM size.

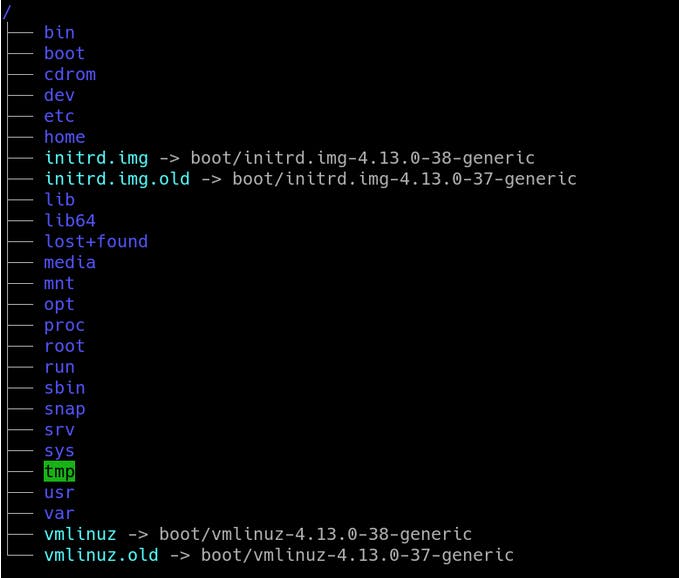

Directories

From top to bottom, the directories you are seeing are as follows.

The / in the instruction above refers to the root directory. The root directory is the one from which all other directories branch off from.

Let's have a look on these directories in detail:

The / in the instruction above refers to the root directory. The root directory is the one from which all other directories branch off from.

Let's have a look on these directories in detail:

- /bin -> binary

It is the directory that contains binaries, that is, some of the applications and programs you can run. You will find the

lsprogram mentioned above in this directory, as well as other basic tools for making and removing files and directories, moving them around, and so on. There are more bin directories in other parts of the file system tree, but we’ll be talking about those in a minute.

/boot -> The /boot directory contains files required for starting your system. Do I have to say this? Okay, I’ll say it: DO NOT TOUCH!. If you mess up one of the files in here, you may not be able to run your Linux and it is a pain to repair. On the other hand, don’t worry too much about destroying your system by accident: you have to have superuser privileges to do that.

/dev -> It contains device files. Many of these are generated at boot time or even on the fly. For example, if you plug in a new webcam or a USB pendrive into your machine, a new device entry will automagically pop up here.

/etc -> Everything to configure It contains most, if not all system-wide configuration files. For example, the files that contain the name of your system, the users and their passwords, the names of machines on your network and when and where the partitions on your hard disks should be mounted are all in here. Again, if you are new to Linux, it may be best if you don’t touch too much in here until you have a better understanding of how things work.

/home -> It is where you will find your users’ personal directories.

/lib -> library It is where libraries live. Libraries are files containing code that your applications can use. They contain snippets of code that applications use to draw windows on your desktop, control peripherals, or send files to your hard disk. There are more lib directories scattered around the file system, but this one, the one hanging directly off of / is special in that, among other things, it contains the all-important kernel modules. The kernel modules are drivers that make things like your video card, sound card, WiFi, printer, and so on, work.

/media -> It is where external storage will be automatically mounted when you plug it in and try to access it.

/mnt -> It however, is a bit of remnant from days gone by. This is where you would manually mount storage devices or partitions. It is not used very often nowadays.

/opt -> This directory is often where software you compile (that is, you build yourself from source code and do not install from your distribution repositories) sometimes lands. Applications will end up in the /opt/bin directory and libraries in the /opt/lib directory. A slight digression: another place where applications and libraries end up in is /usr/local, When software gets installed here, there will also be /usr/local/bin and /usr/local/lib directories. What determines which software goes where is how the developers have configured the files that control the compilation and installation process.

/proc -> Like /dev is a virtual directory. It contains information about your computer, such as information about your CPU and the kernel your Linux system is running. As with /dev, the files and directories are generated when your computer starts, or on the fly, as your system is running and things change

/root -> Home directory of the superuser (also known as the “Administrator”) of the system. It is separate from the rest of the users’ home directories BECAUSE YOU ARE NOT MEANT TO TOUCH IT. Keep your own stuff in your own directories, people.

/run -> System processes use it to store temporary data for their own nefarious reasons. This is another one of those DO NOT TOUCH folders.

/sbin -> /sbin is similar to /bin, but it contains applications that only the superuser (hence the initial s) will need. You can use these applications with the sudo command that temporarily concedes you superuser powers on many distributions. /sbin typically contains tools that can install stuff, delete stuff and format stuff. As you can imagine, some of these instructions are lethal if you use them improperly, so handle with care.

/usr -> The /usr directory was where users’ home directories were originally kept back in the early days of UNIX. However, now /home is where users kept their stuff as we saw above. These days, /usr contains a mish-mash of directories which in turn contain applications, libraries, documentation, wallpapers, icons and a long list of other stuff that need to be shared by applications and services.

You will also find bin, sbin and lib directories in /usr. What is the difference with their root-hanging cousins? Not much nowadays. Originally, the /bin directory (hanging off of root) would contain very basic commands, like ls, mv and rm; the kind of commands that would come pre-installed in all UNIX/Linux installations, the bare minimum to run and maintain a system. /usr/bin on the other hand would contain stuff the users would install and run to use the system as a work station, things like word processors, web browsers, and other apps.

But many modern Linux distributions just put everything into /usr/bin and have /bin point to /usr/bin just in case erasing it completely would break something. So, while Debian, Ubuntu and Mint still keep /bin and /usr/bin (and /sbin and /usr/sbin) separate; others, like Arch and its derivatives just have one “real” directory for binaries, /usr/bin, and the rest or *bins are “fake” directories that point to /usr/bin.

/srv -> data of servers The /srv directory contains data for servers. If you are running a web server from your Linux box, your HTML files for your sites would go into /srv/http (or /srv/www). If you were running an FTP server, your files would go into /srv/ftp.

/sys -> system /sys is another virtual directory like /proc and /dev and also contains information from devices connected to your computer. In some cases you can also manipulate those devices. I can, for example, change the brightness of the screen of my laptop by modifying the value stored in the /sys/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:02.0/drm/card1/card1-eDP-1/intel_backlight/brightness file (on your machine you will probably have a different file). But to do that you have to become superuser. The reason for that is, as with so many other virtual directories, messing with the contents and files in /sys can be dangerous and you can trash your system. DO NOT TOUCH until you are sure you know what you are doing.

/tmp -> temporary /tmp contains temporary files, usually placed there by applications that you are running. The files and directories often (not always) contain data that an application doesn’t need right now, but may need later on.

You can also use /tmp to store your own temporary files — /tmp is one of the few directories hanging off / that you can actually interact with without becoming superuser.

/var -> variable /var was originally given its name because its contents was deemed variable, in that it changed frequently. Today it is a bit of a misnomer because there are many other directories that also contain data that changes frequently, especially the virtual directories we saw above.

Be that as it may, /var contains things like logs in the /var/log sub-directories. Logs are files that register events that happen on the system. If something fails in the kernel, it will be logged in a file in /var/log; if someone tries to break into your computer from outside, your firewall will also log the attempt here. It also contains spools for tasks. These “tasks” can be the jobs you send to a shared printer when you have to wait because another user is printing a long document, or mail that is waiting to be delivered to users on the system.

Digging Deeper